7 June 2018

Rosie Heinrich on how there is no one ˈnærətɪv

review We Always Need Heroes, door Céline Mathieu

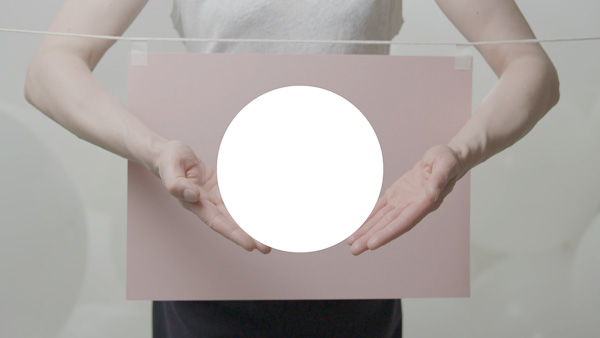

Eat my words, video still from work in progress, by Rosie Heinrich in collaboration with Katrin Hahner

Eat my words, video still from work in progress, by Rosie Heinrich in collaboration with Katrin Hahner

From outside the SYB house, when looking in through the window, a projection shows hand gestures and a face gesticulating. When entering the space it takes time to decipher the video of Rosie Heinrich (UK) who speaks backwards, on a video that is played forwards. The artists’ facial features are accentuated in their muscular presence, as they practice to rewind the undulations and cadence of speech. Each gesture and every attempt work against her natural linguistic instinct, nonetheless she performs calmly. On a fresh pink background, the hands formulate a self-invented sign language. Through speaking backwards, Heinrich stutters and stretches words as well as movements. These glyphs are underlined in subtitles through the usage of her graphic notation system. With it, she marks how language is more than words.

(loosens her lips)

On a second plane, the angelic musical score comes through. Its subtlety is so effective it works as yet another hypnotizing element in the video Eat my words. Its sound is the work of musician and composer Katrin Hahner (DE), who spent two weeks at SYB to collaborate on the new piece. Learning from Katrin that the pure, sweeping chants are actually crushed together bits and pieces of voice recordings, which she refers to as “digested information”, only adds to the bright, crispy way both artists interlocked their practices. Both of them emphasise humbly that this video is just a first rough cut, implying the promise of this collaboration as only the beginning of the journey.

The music works in a subtle, direct way, it sets itself on your midriff and supports the hypnotic quality of Rosie Heinrich’s performance. Seeing her inverted inhalation and pronunciation, she dissects the way we shape words. It is fascinating to see the complexity of our muscle movement, and how each letter is comprised of different sounds. As Rosie puts it, the voice is not a thing in itself, it “repurposes our digestive and respiratory systems”. Using English sayings, “to eat humble pie” and “to eat one’s words”, she reflects on this notion of ingesting* or taking in language.

Thinking backwards to go forwards

For “We always need heroes”, her ongoing project on deconstructing collective narratives, Heinrich has been voice-recording 20 Icelanders’ stories about the 2008 financial crash. In their stories many of the interviewees pointed out they also experienced the crash as a cultural collapse. The extensive recordings of conversations each took one to four hours, and were repeated three to seven times per interviewee. Iceland has a history of sagas and appraises orators highly. In a complicated puzzle, the artist rearranged cuts and snippets to form a new potential narrative from all these stories. This research has resulted in several video pieces and a book, halfway between documentary and fiction, by stringing together pieces of words and pieces of meaning. Not unlike poetry, Heinrich thinks in terms of vocabulary, rhythm, and content. During these long conversations in which people with different backgrounds talk about the crash from a personal and professional point of view, it struck the artist that the interviewees would sometimes say “yes” on an inward breath: “já”. She started getting ears for it, fascinated by how this action paradoxically reverts the word – seemingly subverting its meaning – while “yes” stands for affirmation and presence.

See an excerpt from We Always Need Heroes

In a second room, a pile of A4s big enough to form a wall, testify the administrative workload of the audio transcriptions. By filing and categorising piles of sheets, fiches and post-its, Rosie processed exuberant amounts of text, while collaging the snippets into a new coherent narrative. The complexity and the devotion necessary to re-edit these narratives into one, beautifully mirrors the underlying aim to “make” belief. It highlights the way we can talk for hours, shaping long (personal) narratives. Just imagine her composing all of these into one new coherent thread. It illustrates the confusing idea that the collective only exists out of tiny bits of individual components.

It goes without saying that the artist’s gesture to (de)construct a collective narrative also enables a political reading of the work. But then again, we piece together our own reality, a narrative with frowns and stutters.

In the last space of the house, a large computer screen shows Rosie’s new website. Very much like her work, it has become a play on coherence, using snippets and paraphrases. Due to a peculiar twist of events, I had the opportunity to make a podcast, hence to turn the sound recorder around and have the interviewer talk herself for a change, about self-censorship, make-belief and the sublime. You can listen to her being an “investigator of dialogue and an advocate of doubt” here. With blind spots and broken narratives, it binds the spell.