26 March till 7 May 2015

There’s more place for pathos in literature

Interview by Marian Cousijn

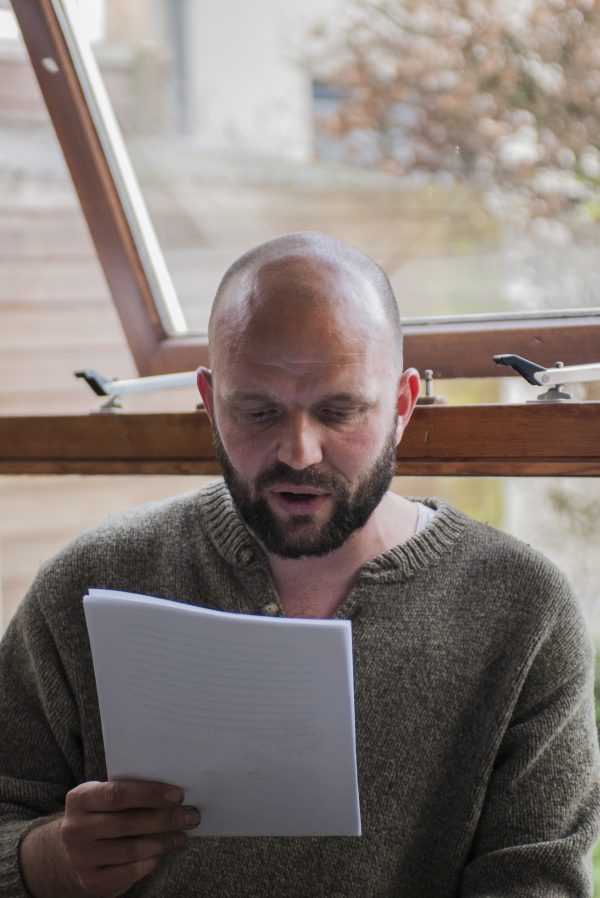

4th May 2015, a sunny spring day. The Netherlands commemorates the Second World War, and in Kunsthuis SYB Pieter Paul Pothoven presents the budding start to the ‘lengthy writing project’ – he refrains from calling it a novel – that he’s been working on these last few weeks. Bathing in the last rays of sunshine behind the house is a smoking vat where Pothoven is smoking the fish he has caught. Moments later they are served on a long table full of bouquets of wild flowers to a group comprising friends, family members and interested parties. In between courses, Pothoven reads passages from his first chapter. At 8 o’clock we hold a two-minute silence.

The entire evening is somewhat reminiscent of one, long performance. Reality and fiction merge during dinner in an extraordinary, sometimes surrealistic manner. The story Pothoven is working on is about the impact the actions of an old resistance fighter have on the generations following him. The texts read aloud tonight were developed in SYB and take place in the surroundings. With compact sentences, visual descriptions and short dialogues, Pothoven renders a crystal clear, almost tangible impression of the awakening Frisian spring.

One of the characters is researching his family history whilst staying in a residence in Beetsterzwaag. He goes fishing with his brother, an eel poacher, and catches a ‘modderhond’: the forgotten freshwater fish gracing our plates this evening. One of the guests at the table, Evere, is an eel fisherman out on the Sneekermeer lake. Pothoven was allowed to go with him a few weeks ago, when they caught the fish that is now lying smoked and sound before us. From Evere’s assenting nods and chuckles at certain passages, it’s possible to deduce that the trip formed a direct source of inspiration for the text now read out by Pothoven. The words are even fresher than the fish on our plates. It’s a strange sentiment: could details from this evening soon also find their way into the manuscript?

The parallels between the story and reality are inescapable. After all, the history of the Kool Family, which this project revolves around, takes its inspiration from the author’s own history.

A week later I speak to Pothoven in Amsterdam. I’m curious about how he experienced the residency at SYB and how he made the step from visual artist to writer.

Pothoven: “I’ve been walking around for years with the idea for a project about the Dutch resistance and my grandfather. Originally from a conceptual approach. I wanted to take a critical look at the gender patterns which have edged their way into war resistance representation since the 1950s: the woman as courier, the man as a tough guy with a gun. In actual fact, women also had leading positions and carried out serious attacks.”

Why did you abandon that idea?

I realised that I wanted to keep it very close to myself: I want to tell a family story in a simple way, not abstract or theoretical. My family partly comes from a working class background, and I find it important that the work is also accessible for them.

To what extent is your story based on your own family?

My own family history forms the point of departure, but everything I write down is fiction. I’m not interested in doing factual historiography. I’m more interested in accessibly describing the role the past can play in the present, in whichever idiotic ways it keeps coming up. It’s definitely partly autobiographical. I can’t get around that. But above all, it’s fiction; nothing has actually happened. Apart from the things that have actually happened…but I don’t want to comment on that.

Does a transition occur from visual arts to writing in your practice?

No, not fully in any case. Although writing is becoming increasingly important to me. At the Gerrit Rietveld Academie I was once told that I harboured more of a writer in me than an artist; I found it utter nonsense at the time. But I’m realising now that there’s more of a place for pathos in literature: for instance, it’s easier to tell a love story. In the visual arts those sorts of things are quickly thought to be too emotional or sentimental.

What is the interaction like between your visual work and your writing?

It’s a different process. I try to consider everything in my art installations, sometimes I’m really gritting my teeth to get it conceptually watertight. The game with language seems to be freer, but I don’t know much about it – I’m just starting out, after all. But I like doing it. I notice that I’m sitting down more often just to write a few sentences, in the way that some people sketch. And when I’m writing, visual ideas often pop up.

What was it like to work at SYB?

Really nice. I realised that I didn’t actually need anything. I didn’t speak to anyone for two weeks. I got up at 7 a.m. and wrote until 12 p.m. After that I went for a walk, made dinner, and then I spent another few hours writing in the evening. If it were possible, my days would look like this for the rest of my life.

The ‘modderhond’ played an important role during the presentation. Where does your fascination for this fish come from?

I really wanted a fish to become part of the story. During my research I stumbled on the tench: a beautiful and somewhat secretive fish with red eyes. It turned out to be called mûdhûn in Frisian, meaning mud dog. It spends most of its time lying still in the mud. That fitted well with one of the characters in the book, someone who’s also more or less lying in the mud. I can really imagine myself as that fish.

The story of the mud dog is also a parable for me: it starts as a radiant spring day and becomes more and more painful, until suddenly you’re completely stuck.

I found it really special that you wanted to share your work in this early stage: the text was still really raw. No doubt countless sessions of corrections, editing and rewriting will follow. What was it like to present your book in this embryotic stage?

I was advised not to, but to me it seemed like a good lesson to open myself up, even though I was far from certain as to whether it was any good. It’s very different with my visual work; which doesn’t leave the building until I think that it’s exactly right. But in this case I consciously organised an informal setting. It was an interesting exercise, I could tell from the reactions what worked and what didn’t.

The residency at SYB is now over. What are your further plans with the book about The Kool Family?

The approach per chapter works well. I’m already fantasizing about the next sections. Maybe some of it will take place in Brazil. But this opening chapter needs to be finished first. I’ll be presenting the final version during the SYB Triennial Sfear fan Ynset in September. Then I’ll be catching fish again and smoking them in a vat, and I’ll be reading stories every day of the exhibition.