28 till 28 June 2015

NO SOLID GROUND

Review by Anne Marijn Voorhorst

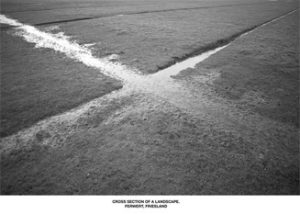

CROSS SECTION OF A LANDSCAPE #2 – Yeb Wiersma & Miek Zwamborn

Dressed in shorts we lift our legs, clay sticking to our feet, from the soles up to the calves. I cannot hear anyone talking, the wind on the mudflats has free rein and sweeps into all ears.

Never before have I seen such an equal distribution between air and soil. While I notice how my body adjusts itself to these circumstances, my head does not function anymore – it just floats. The air suppresses my thoughts and my feet just want to plow. Ahead, the destination beckons – a void awaiting to be filled by our bodies.

Today, we are the researchers of mud flats. The overwhelming space and horizontal lines of our journey called ‘No Solid Ground’ stand in stark contrast to Yeb Wiersma and Miek Zwamborn’s previous expedition ‘Cross Section of a Landscape’, a walk through the woods of South Limburg. Their journey was dominated by the dense vegetation and details of plantations. Led by a botanist, they walked this route that was enriched by the quotations and images from their own work and those borrowed from other writers, amateurs and scientists. This time Yeb opens the excursion by reading a piece from the book Aquaphobia, Tulip Mania, Biophilia: A Moral Geography of the Dutch Landscape by philosopher Hub Black:

“(…) Roman visitors were most of all struck by the formlessness of this vapor and airy world, by the lack of clear distinctions between land and water. (…) It was an environment, so to speak, without a face.”

The quagmire slurps and pulls, and forces us to reinvent how we walk. The smell of rot rises from the deep in the ground. The sludge is a soil that endures both high and low tides, explains our guide Rob. The top layer withholds the subsoil of oxygen but the plowing of our feet introduces air to the sunken organisms releasing an odor that is rancid to us.

That distant line that separates air from earth also marks the body with a dash: everything from the hip to the head becomes weightless. Our sense of time evaporates, making our bottom halves (from the pelvis to the toes) arduous and serious. The division confuses us; one part aspires to drift off like a helium balloon, while the other wants to dig into the mud like a mole.

We leave lines behind us that do are not as straight as we had hoped. Judging by our tracks, we look like wavering drunkards. Suddenly, millions of small twists appear on the ground in front of us the feces of lugworms, which looks exactly like they do. Imagine, I thought, if all animals defecated their own replicas there would be no space left to live.

We gather around Miek. She plants two bamboo sticks in the mud flats and attaches a few papers that seem to be protesting as they flutter in the wind. We can discern images of the Tidal Series (1969) by the Boyle Family. Miek tells us about the work, which consists of fourteen studies of a single square meter of beach at Camber Sands, near Sussex. The artists captured the surface twice a day for a week with twelve-hour intervals. They used resin and fiberglass to encase the sand structure, which varied every time due to the change of tides and weather conditions. The artists say they were unable to influence the resulting forms of the works beyond the choice for that specific location.

We embark on our return journey. We leave behind the horizon that carries the contours of Terschelling, and turn our gaze towards the belfries and green land.

We see a trail of our own hour-old footsteps in the distant clay, still seemingly fresh. Traces do not disappear just like that. Just like a glass bottle on the side of the road takes about a million years to decompose, footsteps on the flats take about six hours until they vanish by the hands of the next high tide.

In the void hides the entity. I notice, while the ground under our feet becomes increasingly solid. Salty, dry chunks of land on which one rebounds. The cracks determine the rhythm of the landscape. Farewell to forests of salicornia and frantically squeaky avocets and oystercatchers.

The return of stability, the grass lawn leading up to the dyke. The yellow of the buttercups and green of the grass seize my eyes as if I am hallucinating. Here I discover that the idea of a stable horizon is just an illusion, as it swings and sways like a current. I put some samphire in my mouth to make sure my hallucinations are not caused by hunger.

After changing into clean, warm clothes, we sit down with Louwrien Wijers and Egon Hanfstingl. The bowls of steaming ‘Blissful Peace Soup’ prepared by Egon bring us back to an environment that seems suddenly unfamiliar. Louwrien tells of her encounters: Andy Warhol,

…