6 November till 20 December 2013

PERCEPTION IS SUBJECTIVE

Review by Tanja Baudoin

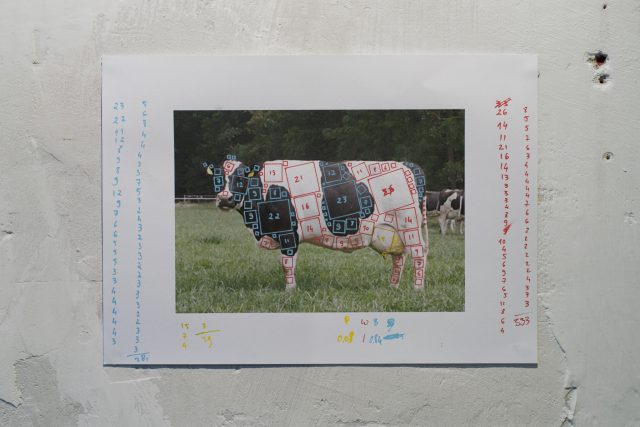

According to farmer Geert Geerligs a cow is a “four-hoofed animal with udders under it”. Geert is convinced that a cow can be recognised from a significant distance. Something Tom Kok put to the test. In SYB he presents, among other things, a framed photograph of a field in which there are two white flags with squares of black fabric sewn onto them. The abstract flags certainly can’t be confused with cows, but do create a powerful image in the landscape, a landscape that in itself is the result of a tidy ordering of squares.

The photograph captures the realisation of a thought experiment that Kok carried out during his residency in SYB. The original experiment is a philosophical example of a so-called ‘Gettier problem’, that postulates a case study concerning a farmer looking for his favourite cow. The farmer sees his cow in the field standing next to a tree and tells this to his farm-hand with a sense of relief. The farm-hand subsequently goes looking for the cow in the field and doesn’t find the cow next to the tree but behind a hill. He sees that a piece of black and white paper was blown into the tree, leading the farmer to think that his cow was stood there. Did the farmer actually know whether his cow was in the field or not? He possessed the right knowledge, because the cow was there, but his conviction was not based on a correct perception.

Kok has collected similar thought experiments from the fields of philosophy, ethics and science and attempted to carry them out in and around SYB. The experiments focus on contemplating a particular theory or problem. The difficulty is that they’re not devised to actually be carried out, but draw up a hypothetical situation to which a singular answer cannot be given. Kok argues that they fundamentally undermine the principle of objective knowledge, because as soon as you reflect on a case study, an appeal is made to your subjective powers of imagination. The experiment takes place in your private thoughts and therefore touches upon the fundamental question of whether knowledge is able to exist independent of ourselves.

Kok’s interest in epistemology can be viewed in light of a tendency in contemporary art practice, which questions what can be understood under knowledge and how this can be gained. Many of these practices criticise institutionalised knowledge forming, demand attention for unconventional knowledge production or focus on the creation of alternatives. A wide range of artists concern themselves with this problem, from Erick Beltrán who compiled an encyclopedia of the personal theories of people (The World Explained, among other places on show in the Tropenmuseum, 2012), to the Copenhagen Free University (Henriette Heisse and Jakob Jakobsen) – an early example of a series of pedagogical initiatives started by artists in the past decade. These projects share the fact that they pose critical questions with regards to the criteria of academic and scientific knowledge production and to the financial interests behind the development of the ‘knowledge economy’.

The work of Tom Kok attaches value to subjective knowledge production and as such is in keeping with this tendency. But Kok isn’t concerned with undermining the thought experiment. Instead, he is seeking out the theory’s boundaries, exploring its mechanism from the inside out by giving it a form. What’s most interesting is that in doing so he makes a representation of something that in essence is ‘imaginary’; he makes the visual component that’s enclosed in the experiment tangible. Kok seems to suggest that we shouldn’t underestimate the form as this can also contain knowledge.

In SYB, Kok presents a video interview with local farmer Geert Geerligs, the photograph of the flags in the field, various prototypes of the flags, a clay table with tent pegs used to fasten the flags in the field, books with descriptions of thought experiments, a self-constructed set for an experiment yet to be carried out (the Chinese Room, the film shoot has since taken place), a series of screen prints, and objects that arose from a dialogue with the artist Priscila Fernandes, who joined him for several weeks in SYB. This display of work, research material and work-in-progress leaves no doubt that Kok has worked incredibly hard over the last few weeks.

The overwhelming amount of work does raise the question of how the research in thought experiments is transformed into an artwork and whether this work perhaps belongs in a sequence of steps. Or is the execution of the experiment, such as what happened in the field, the actual artwork? The photograph of the flags suggests something different. This photograph is not purely a documentation of the action. It is rather that the realisation of the experiment in the field served to create the photographic image. A composition has been made that demands a particular point of view, with the horizon in the background, a flag next to the tree in the middle, and the other flag in the foreground. The photograph is the product of this precise staging, one that’s made complete during the SYB presentation with accurate lighting and a self-constructed frame. The other displayed works hereby gain the status of props, which have played a role in the creation of that image.

What’s particularly successful about the image is that it can’t be reduced to the result of an experiment, but that it seems topropose something to the viewer itself, a constructed given that stimulates the thought process. Kok’s photograph combines materiality with abstraction and therefore transcends the subjective realisation of the experiment. It confronts the viewer with a tableau, the meaning of which is not immediately divulged, despite the narrative of the case study filtering through. Moreover, the medium of photography is a challenging choice for making a ‘concrete image’ in response to a ‘concept image’, precisely because it can be so mercilessly real.

The relation between an idea and an object and the possible severing of the two has been an important subject in visual art at least since the ’60s . The conceptual art that emerged in that time supposedly attached more value to the idea as the origin of the artwork and less to the execution of it. What’s actually at stake in this art is the meeting of the concept and the material carrier, and the tension that arises from it. With this presentation ‘Pumping Intuition’ Tom Kok gives his own accents to this meeting and therefore, in conclusion and contemplation, a selection of several points from Sol LeWitt’s Sentences on Conceptual Art (1969):

The artist cannot imagine his art, and cannot perceive it until it is complete.

Ideas can be works of art; they are in a chain of development that may eventually find some form. All ideas need not be made physical.

A work of art may be understood as a conductor from the artist’s mind to the viewer’s. But it may never reach the viewer, or it may never leave the artist’s mind.

Irrational judgements lead to new experience.

Perception is subjective.

translation: Jenny Wilson